HRV4Training

|

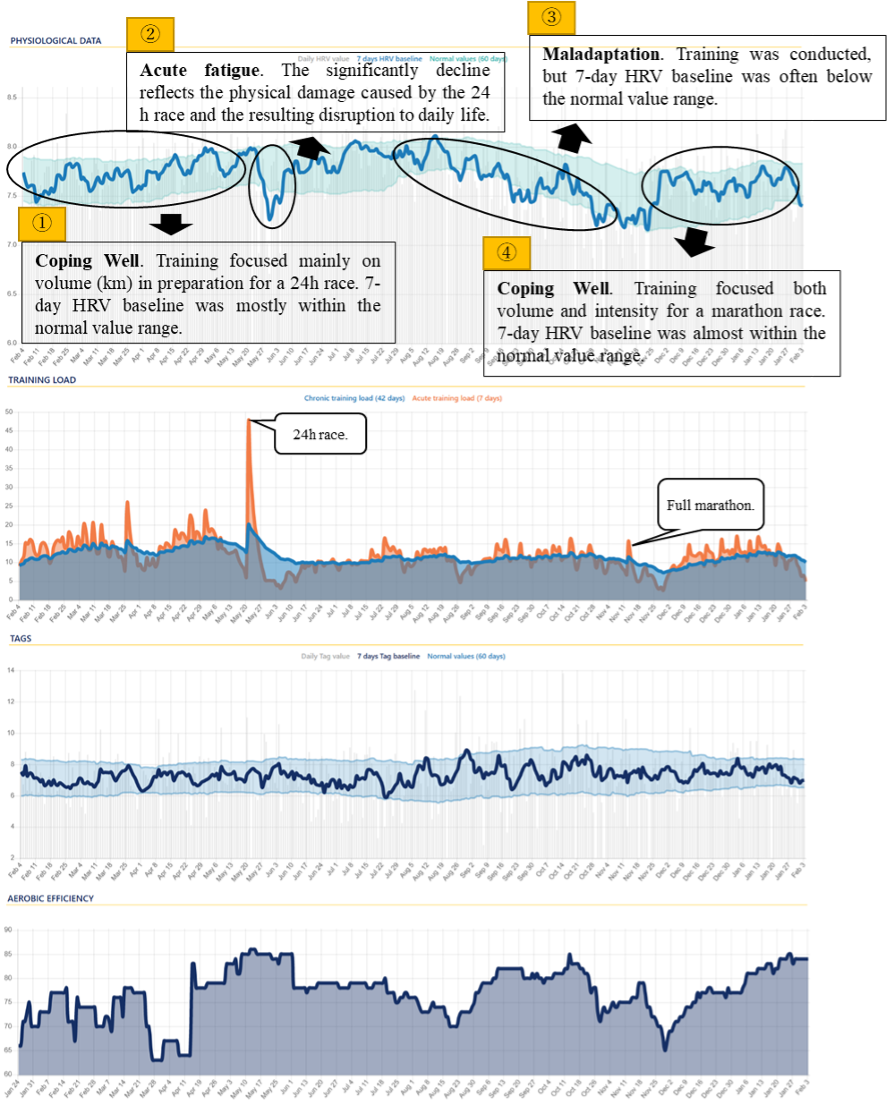

This blog and case study was written by Fuminori Takayama. Fuminori is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) with a Ph.D. in Health and Sport Sciences. He currently works as a strength and conditioning coach for athletes alongside a researcher. He is also an amateur runner. This article is a discussion of his HRV, training, sleep duration, and aerobic efficiency data for the past year. If you have any questions, comments, or inquiries, please contact Fuminori here. Data collection HRV and sleep duration was collected with an Oura ring. Training data was collected with Garmin GPS watch and Polar sensor (OH1 or Verity Sense). All data was read in HRV4Training and analyzed in HRV4Training Pro in the long term. For more information about aerobic efficiency, see this article. Contextualization of the past year's data As shown in Box1, this period was a training phase for a 24h race held in late May. The purpose of training is to increase volume (km). Training included long-distance running (40-80 km/session) and frequent jogging (about 15km/session). I checked HRV frequently and was careful not to increase the training load when the HRV was trending down. I felt that the approach may contribute to a stable HRV (and a slight increase in HRV). Although I was unable to break my own record from eight years before (181.690km), I was able to perform to a high standard in the race (171.760km). You can read about my approach to the race in this peer-reviewed paper. As you can observe in Box 2, the HRV was significantly decreased after the 24h race. This may reflect the damage done throughout the race. However, after the race, my eating habits were disrupted for a while (consuming a lot of junk food). In any case, the disruption of lifestyle habits that tends to occur after a high priority race may be add to the damage caused by the race.

Now let’s look at the third box. For the marathon in mid-November, I started specific training around September. During this period, the HRV was sustainably decreased. Interestingly, aerobic efficiency had also worsened. Although I improved my marathon personal record in the race (2:57→2:56), I was unable to clear my target time (2:54). In fact, I think the reason for the PB came from the benefits of the carbon plate shoes. Why did my HRV continue to decline, and aerobic efficiency worsen? I don’t understand exactly but feel that factors other than training are involved. Seasonality in resting physiology could also play a role here as HRV is often reduced during winter months. In the fourth box we can see that I resumed training in early-December for the marathon in early-February. A very important factor is that after the marathon in mid-November, I experienced poor running performance, so I avoided specific training for about half a month. I felt that the half-month break was beneficial for both physical and mental recovery. The training concept from mid-December is very simple. In short, it included the following four items.

Due to a death in my family, I needed to go back home and was unable to participate in a marathon race in early-February. If I had participated in the race, I would have had the chance to improve my PB significantly. However, sometimes life sets priorities more important recreational running. I felt I could tolerate well training stress, as shown my HRV, but not non-training stress (as evidenced by the last few days of suppressed HRV). Here is just one example, contextualization of various data and HRV is useful in securing both performance and health improvements in recreational and elite athletes. HRV4Training and HRV4Training Pro are the best tools to facilitate the contextualization procedure. Comments are closed.

|

Register to the mailing list

and try the HRV4Training app! |